It’s sunset on Botswana’s Serondella floodplain, and all is not as it should be. In past dry seasons, this plain was filled from bank to bank by the Chobe River, which courses over 750 kilometers of south-central Africa. But this year is different. Long grasses stand where large swaths of river once flowed. Boats navigate to the middle of the channel. The river has narrowed, and the land is in the grip of drought.

Rivers always gather life to them, and this is never truer than in a drought. As evening falls, many species descend on the depleted Chobe: lions, giraffes, eagles, buffalo, hippos, egrets. But none is as arrestingly visible as the African Bush Elephant.

Elephants are deeply social. From our tiny boat nosed up on the bank, we watch a herd appear, head matriarch at the fore — elephant families are led by females — with youngsters running to catch up. Other elephants converge with the group as they move toward the water. They have come to drink and socialize.

Some of their communication is obvious, such as touching each other with their trunks. Some is not: they are likely making vocalizations beyond the range of human hearing.

We watch the approaching herd with interest, then trepidation. They could choose anywhere along the many miles of riverbank to drink yet seem to be heading — yes, directly toward us. Seeing earth’s largest land mammals ploughing toward you is unsettling.

But they keep coming, getting closer, closer — until they have gathered around us, just a few feet away. We look up from within their shade; I am feeling small and fragile. The giants peer down with red-brown eyes. It is hard not to read curiosity there. Then they get about the business they came for: drinking, dunking, playing.

It’s a peaceful encounter — but not all such encounters are. Later that day, we watch a three-story riverboat laden with cocktail-drinking tourists sail right up to an elephant, causing her to move off. Another evening, a hulking boat comes within inches of hitting an elephant as she fords the river. The pilot realizes the danger at the last second, gunning the engine to maneuver away.

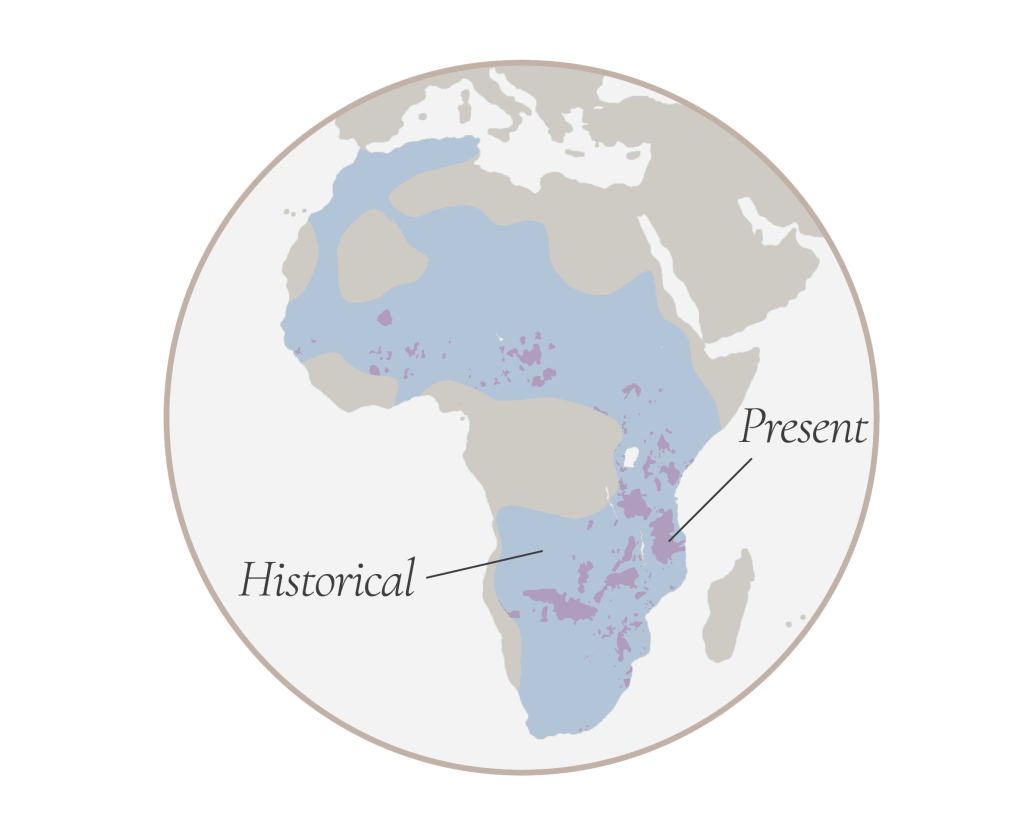

Other human-elephant conflicts are land-based. Since the beginning of British colonization, Southern Africa has been carved up for logging, mining, and farming, creating new and risky interspecies encounters.

Elephants — both Bush Elephants and their close relatives, the Forest Elephants — will happily raid crops and plantations; residents, in turn, will take measures to get rid of elephants and prevent economic losses, including frightening or poisoning them. Such interactions intensify stress for human and nonhuman players alike.

Habitat fragmentation creates other challenges. Many elephants travel long distances — 100 miles or more — with the turning of the seasons. These are traditional routes walked by generations of elephants. Land development disrupts these longstanding practices.

Hunting, too, is a major concern. Trophy hunting is legal in Botswana, the last stronghold of wild African Bush Elephants. Ivory poaching is also a problem, and has led an increasing number of elephants to be born tuskless — a visible signature of human impact.

All of this is to say that elephants are deeply endangered. While conservation work is often most effectively done where a person lives, anyone in or out of Africa can donate to organizations that support elephants by working to stop poaching, end the ivory trade, and reduce human-elephant conflicts.

Consumers can also choose not to buy products containing palm oil, which is often produced on plantations that further carve up elephant habitat and lead to negative interspecies encounters.

But the situation remains difficult. The African Bush Elephants that gathered to observe us on the drought-ridden banks of the Chobe are among the last of a certain version of this species, in both appearance and way of life. Not all of the giants who came to visit us will survive the dry season; we saw many elephant skulls, many pieces of leathered skin baking in the sun, many signs of the supreme difficulty faced by life in this era of global warming.

The simple reality is this: a lot of work remains to ensure the survival and flourishing of African Bush Elephants, with their intimidating curiosity and intergenerational ways of being.